Mad in Pursuit Notebook

The Family Land: Ballaghduff

In May, 2007, on a misty evening, Carmel Ghee took Jim and me to visit the remains of Ballaghduff. Maura Stephens met us there at her Uncle Paddy Kilmartin's house, where he grew up under the watchful eye of his Uncle Mike Dunne. Paddy had recently passed away and his border collie Gypsy refused to leave the premises.

I found the texture of the land to be as mesmerizing as Ireland's rocky coasts. As a city girl,I wanted to know more. How did it all work?

Some history

To get a flavor for life in Ballaghduff, you really have to read Josephine Collins's beautiful essay on the subject.

In 2000, 18 residents of Kilkerrin (County Galway) participated in a Certificate Course in Local History and produced a book called A Place of Genius and Gentility: Insights into Our Past [4]. Josephine (married to our cousin Paddy) was on the Editorial Board and contributed a chapter on "The Townland of Ballaghduff."

A sample. Our cousin Philomena Stephens Kelly (1931-2000) was a school teacher who described the land to Josephine in an interview [4]:

Fr. Glynn... re-named Ballaghduff Tír na nÓg [Land of Eternal Youth]... We could field a team for a hurling match in Wall's field or a football team for a game in the lanes in Milltown... Our social life lacked nothing. A princeam (from the old English word "prinkum," meaning a caper or house dance) was organised in a few hours and these took place regularly. Our musicians were locals who played fiddle, tin whistles, and in later years, the accordion. Songs were sung, poems recited and stories of other days were told. Gaelic words were used frequently and traces of the Gaelic era are found in the names of fields and gardens. In our village, Baile Thoir (east), households had narrow strips of land called "gits" probably from the Irish word giota, a small portion.

The beairnín or bearnán rua (translated as little gap or red gap) was a name given to fields in a part of the village where the grass took on a reddish hue in the autumn. Then there was Coiléir an Áirne (quarry of the sloe), Moínín Árd (high meadow) and Moín Guail or gcúl (bog of the hard, black turf or back bog). This word moín was pronounced "moon" which is the western Gaeltacht pronunciation. Gort a' bhealaigh was another field name. It got its name from the path to school through the fields. Between Ballaghduff and Clooncunore are the askeys, from the Irish, eascaí, low-lying land by the river. One field was called the flax field, as flax was grown there. The "tow" was the rough or discarded flax. Men wove a plait of this to repair the flail. Linen sheets, towels and tablecloths were in every house. In the words of the poet, Wordsworth, "Bliss it was in that dawn to be alive. But to be young was very heaven."

Josephine also looked further back in time and found that the townland had been occupied for 250 years. I researched what I could from the 19th century. Here are a few highlights.

1827

The Tithe Applotment survey was conducted to collect a tax to support the (Protestant) Church of Ireland. While Ballaghduff was a thriving little community back then, only John Stephens (1798-1876) is listed as the "occupier" of the east and west villages. This is because Ballaghduff operated as a rundale, a form of primitive communism, where one resident collected the rent from all the others to pay the landlord, Rev. Hyacinth D'Arcy of Clifden. John Stephens had this leadership role. He was our counsin Maura Stephens's 3rd great-grandfather on her father's side.

Rundale farming systems in Ireland existed from the Early Medieval Period right up until the time of the First World War.

The rundale system of agriculture consisted of nucleated villages known as clachans...

The main "clachan" area where the small thatched cottages were concentrated, was situated in a cluster on the best land (the infields) which was surrounded by ... grazing land of inferior quality (the outfields) where the livestock was grazed during summer or dry periods, a practice known as transhumance or as "booleying"... In the remote western areas of Ireland where the rundale system was most commonly seen, the land was a complex mixture of arable, rough and bogland. It was a difficult task to ensure that each tenant had an equal share of good and poor land. [Wikipedia]

1850

Food and landlord anxiety. Here we are, deep in the Great Famine (An Gorta Mór). Lacking potatoes, the residents of Ballaghduff were able to survive on their oat crop. But their landlord Hyacinth D'Arcy was in trouble. His father had mortgaged the family's two large estates (Kiltullagh and Newforest) to the Englishmen Thomas and Charles Ayre (aka Eyre). As Ireland plunged deeper into poverty, many over-mortgaged landlords couldn't pay back their loans. England created the Encumbered Estates Court to auction off their property.

The "Newforest" (aka Morganure) estate auction included the townlands Morganure, Furhill, Ballaghduff, Miltown, and Currelehenagh East and West. The land ultimately went to Thomas Ayre. The D'Arcy family continued to maintain their posh estate in the nearby townland of Newforest.

1856

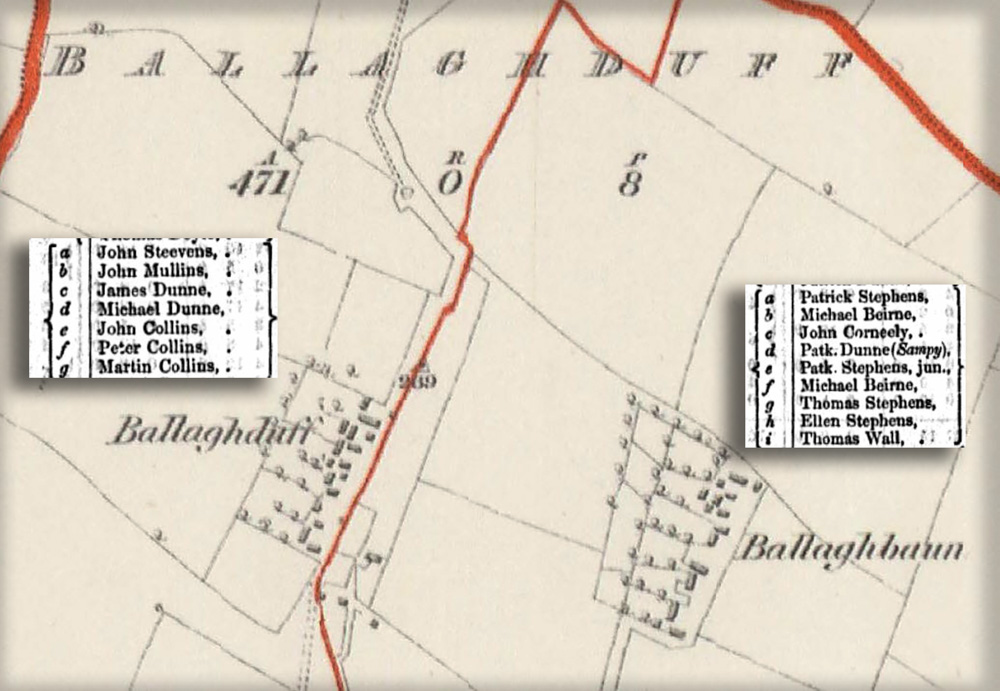

In 1856, Griffith's Valuation [3] listed 8 parcels worked by about 25 families, with the two largest areas run by 8 and 9 families each. It was about this time that the 40-year-old bachelor farmer Michael Dunne (the elder, abt. 1817-1885) married Eleanor Stephens (abt.1830-?) and began their family.

1901

By my grandmother's day at the turn of the 20th century [1], the property at Ballaghduff was worked by seventeen families who lived in two clusters a few hundred feet apart. About a third of the 471 acres was bog. The rest was rated from "good" to "poor" as farmland goes.

The Michael Dunnes lived in a "2nd Class" dwelling (whitewashed stone walls, thatched roof, 3 rooms [kitchen/living room and 2 bedrooms], 3 windows in the front), where they raised nine children. Their three outbuildings consisted of a stable, a cow house, and a barn.

20th century

The mid-19th-century shock of famine—bringing death by starvation, disruptions in property ownership, and massive emigration—continued to ripple into the 20th century. Young adults left the rural villages in droves. Back-breaking farming gave way to raising cattle, which was more profitable.

Now, for most of us, Ballaghduff exists only in our imaginations—our people—overcoming hardship with joy, always in our hearts.

Notes

[1] Irish Census 1901

[2] Throughout the 19th century Irish peasants rented from landlords, in my family's case from the D'Arcys (web article). Early 20th century land reform finally allowed tenants to purchase.

[3] The Tenement Act of 1842, now known as Griffith's Valuation, required an evaluation of every parcel of land for productivity. In the absence of census data, it's a useful source about info about communities.

[4] A Place of Genius and Gentility: Insights into Our Past. © Oidhreacht Chill Choirí, 2006. Published with private local funding.

5.29.07 (rev. 5.30.07, 6.2.18, 4.13.2025)

All pages in this website by Susan Barrett Price are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License.